James Donaldson notes:

Welcome to the “next chapter” of my life… being a voice and an advocate for mental health awareness and suicide prevention, especially pertaining to our younger generation of students and student-athletes.

Getting men to speak up and reach out for help and assistance is one of my passions. Us men need to not suffer in silence or drown our sorrows in alcohol, hang out at bars and strip joints, or get involved with drug use.

Having gone through a recent bout of depression and suicidal thoughts myself, I realize now, that I can make a huge difference in the lives of so many by sharing my story, and by sharing various resources I come across as I work in this space. http://bit.ly/JamesMentalHealthArticle

PHOTOGRAPHED BY EYLUL ASLAN.

Warning: This feature contains references to self-harm and suicide which could act as triggers to some readers.

The link between mental ill health and social media, particularly among younger generations, is old news, but the recent coverage of 14-year-old Molly Russell’s death by suicide has made many members of the UK establishment sit up and finally listen.

After Molly took her own life in 2017, her family were given access to their daughter’s social media accounts and were alarmed by the content she’d been following. They found distressing material about depression and suicide on her Instagram account, and her father Ian has publicly blamed the social media platform for its part in the death of his daughter. It also emerged that Pinterest emailed Molly a month after she died with 14 graphic images showing self-harm.

Since Molly’s story came to light, the government has promised to do more to tackle harmful social media content, with suicide prevention minister Jackie Doyle-Price saying this week that the tech giants must “step up” to protect vulnerable users, and digital minister Margot James insisting that she “will introduce laws that force social media platforms to remove illegal content, and to prioritise the protection of users beyond their commercial interests.”

Instagram claims it “does not allow content that promotes or glorifies self-harm or suicide and will remove content of this kind,” and announced this week that it will introduce “sensitivity screens” (which will blur some images and text) in an attempt to shield young people from self-harm images. But currently, as we found, dangerous content is still readily available with a few clicks. All it takes is a quick Google search and anyone can find a catalogue of harmful content on Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook, Tumblr and Twitter.

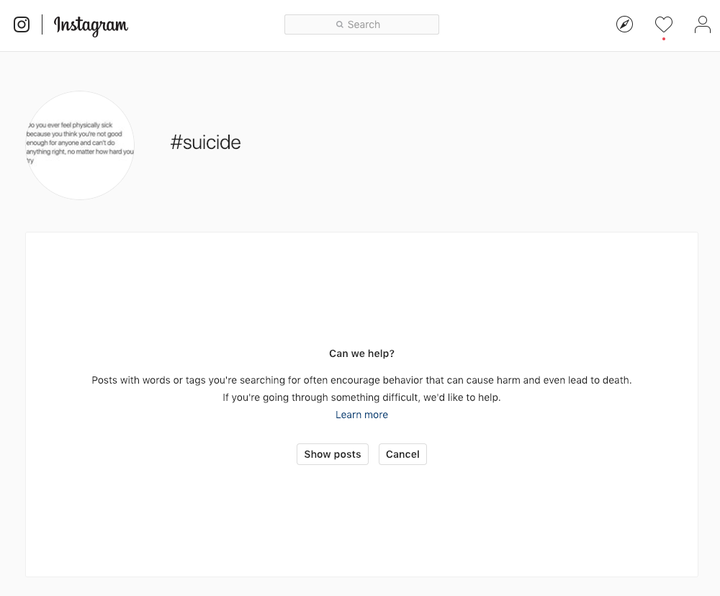

INSTAGRAM’S SAFETY MESSAGE FOR SEARCHES OF THE WORD “SUICIDE”

Searching the word ‘suicide’ (and other ‘trigger’ search terms like ‘depressed’, ‘anorexia’ and ‘unwanted’) on Instagram brings up a warning (pictured above) offering a link to support: “Posts with words or tags you’re searching for often encourage behaviour that can cause harm and even lead to death. If you’re going through something difficult, we’d like to help,” it reads.

Clicking on “Learn More” takes you through to a page on Instagram’s website which reads “Can We Help?” and gives you the options to message a friend or someone you trust, to call or text a trained volunteer, or to get tips and suggestions of ways to support yourself.

However, if you choose to ignore those suggestions and simply click “Show Posts” then damaging and dangerous content is immediately available, including pictures of nooses, quotes that normalise suicide, and tearful voice recordings of people struggling with their mental health.

While other harmful topics appear to have been blocked completely on Instagram, searching for ‘self harm’ still brings up handles which contain the words. Some accounts are private, others are not. Within a minute of browsing through these accounts, you can find alternative self-harm hashtags in image captions that are currently in use, which are often amalgams of similar words and phrases. This, coupled with the fact that Instagram’s algorithm is engineered to show people content they’re interested in, has led to allegations that Instagram is ‘complicit’ in deaths like Molly’s.

Refinery29 contacted Instagram on Wednesday, and the site has already removed a self-harm and suicide-related account that we flagged as an example. An Instagram spokesperson told us the company has “started a full review of [its] policies, enforcement and technologies around suicide and self-injury content.”

They continued: “While we conduct this review, over the past week we have had a team of engineers working round the clock to make changes to make it harder for people to search for and find self-harm content. We have further restricted the ability for anyone to find content by searching for hashtags and in the Explore pages, and we are stopping the recommendation of accounts that post self-harm content.”

On Pinterest, searching similar trigger terms brings up a warning: “If you’re in emotional distress or thinking about suicide, help is available,” with a link to the Samaritans website. Pinterest told us it “just made a significant improvement to prevent our algorithms from recommending sensitive content in users’ home feeds,” and will soon introduce “more proactive ways to detect and remove it, and provide more compassionate support to people looking for it.”

On Twitter, searching for some of the most common words and phrases, like ‘self harm’ and ‘suicide’, yields results that come with no warning message, and there is no offer of help.

A Twitter spokesperson told Refinery29 that “protecting the health of the public conversation is core to our mission”. They added: “This includes ensuring young people feel safe on our service and are aware of our policies and products which are purposefully designed to protect their experience on our service.” It provides information about suicide prevention on the app and on the web and a form to report self-harm content.

Harmful content is also going undetected by social media platforms under the guise of outwardly positive hashtags like #mentalhealthawareness, #mentalhealth or #suicideprevention, says Charlotte Underwood, 23, a mental health advocate, freelance writer and suicide survivor who frequently sought out harmful content online during her teenage years. “While these hashtags are used a lot for people who are advocating and trying to find ways to help reduce mental health stigma, sometimes you find triggering pictures and posts that are worrying,” she tells Refinery29. “Though sometimes this means that the person posting can be helped and supported, which is a positive, despite the dangers of triggering posts.”

All people need to do is type in the words in a search bar and they can find it. The truth is, it’s not difficult to find this content and that’s a huge problem.

Underwood has also noticed the rise of specialist accounts dedicated to sharing certain harmful content. “Some are well looked after and removed for ‘potentially triggering’ content, but others will not have any filters. All people need to do is type in the words in a search bar and they can find it. The truth is, it’s not difficult to find this content and that’s a huge problem. When it’s easier to find harmful content than to access appropriate healthcare, it’s concerning.

As a young teenager, Underwood would use Tumblr to find others going through what she was feeling. “I vividly recall hunting down self-harm posts and posts on suicide because I wanted to validate my feelings and know that I wasn’t alone. As scary as this content was and still is to this day, it was the only thing that made me feel like I wasn’t alone.”

Her searches often led her down a dangerous path and proposed ideas of new ways to harm herself. “I now can’t look at a picture like that because I know how it made me feel back then, and [I] will instead report and mute the picture.”

The content is out there whether it’s on social media or not.

The truth is, harmful content is readily available all over the internet – not just on social media – which the government seems to be forgetting. “Initially the content I looked up wasn’t on social media, which is really important to note – this content has always existed outside of social media and will likely continue to exist outside of social media; the problem doesn’t start and end there,” says 25-year-old Lisa, a mental health advocate and blogger, who self-harmed daily and had persistent suicidal thoughts in her younger years. “In the beginning it was forums and sites I’d found on Google. I think I’d been researching the ‘best’ methods of harming myself and went down a rabbit hole.”

Lisa says she’s come across very little harmful content on social media herself, “although it clearly does exist across multiple platforms. Nowadays, I see social media full of exactly the opposite sort of messages; people sharing hope, coping mechanisms and crisis resources for people struggling.” Her real worry, again, is the Wild West that is the rest of the internet. “The big social media companies absolutely have a duty of care about what is shared and viewed on their platforms. But ultimately, the content is out there whether it’s on social media or not. The real issue is that there are simply not enough mental health resources out there.”

Many experts in mental health and social media also believe the government’s latest proposal doesn’t go far enough. Andy Bell, deputy chief executive at the Centre for Mental Health, told Refinery29 that while “there may be merits in exploring a ‘duty of care’ for social media providers,” it’s not black and white. “We need a more balanced debate about the potential benefits of social media interaction for young people’s mental health, as well as seeking to ensure that safety is prioritised.”

Mental health is influenced by many different factors, Bell adds, “and we need to work with young people to ensure that social media can play a helpful role in supporting wellbeing as well as taking the necessary action to keep young people safe.”

Sonia Livingstone, an LSE professor who specialises in children’s rights on- and offline, and a blogger on digital parenting, says she’s yet to see adequate statistics on how much harmful content is available or how accessible it is. “That’s part of the problem. If there is legislation, how will we track improvements?”

There’s also a risk that overzealous legislation could end up prohibiting positive mental health content. “Ideally we’d find an effective way of distinguishing self-help community content from harmful content that exploits our vulnerabilities. I’m worried that tech solutions can be heavy-handed over such sensitive issues, so public oversight of tech regulation is vital.”

Many in the charity sector are impatient with social media companies’ repeated assurances that they’re already doing all they can to protect users. “With a few clicks, children and young people can have almost unlimited access to suicide and self-harm content online – despite tech giants claiming they prohibit such material,” Tony Stower, the NSPCC’s head of child safety online, told us. “Social media sites show a warning on one hashtag with harmful and distressing content, but then simply suggest multiple alternatives without any warnings whatsoever.”

Tom Madders, campaigns director at YoungMinds, wants social media companies to take responsibility for the potentially dangerous impact of their algorithms, “making sure that [they] actively promote mental health support rather than steering users towards similarly distressing material.”

If you are thinking about suicide, please contact Samaritans on 116 123. All calls are free and will be answered in confidence.

If you or someone you know is considering self-harm, please get help. Call Mind on 0300 123 3393 or text 86463.