In November 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported an increase in the age-adjusted suicide rate since 2021. The report details that in 2021 and 2022, people ages 75 and older had the highest suicide rate among all age groups, largely driven by males. This report is a salient indicator of the challenge of identifying and addressing suicide risk among older adults amidst the well-publicized mental health crisis in the United States. Underpinning this profound challenge are the direct connections among social isolation, neglect, and suicide.

The population in the United States is rapidly aging. In 2020, adults ages 65 and older comprised nearly 17 percent of the population, and this group is growing at nearly five times the rate of the overall population. Older adults face a unique set of stressors associated with aging: decline in physical health, reduced mental acuity, shrinking social networks, and losses of friends and loved ones. These stressors may compound the impacts of mental illness initially experienced at younger ages. In some cases, they lead to diagnosable mental illnesses, most frequently anxiety and depression, while in other cases, they create bouts of distress that do not meet the clinical criteria of a diagnosis.

Within our current model of care, a diagnosis is given in the context of the services and programs that are provided in the medical system. As a result, most efforts to mitigate suicide have a strong clinical focus. However, both diagnosed mental illness and subclinical mental distress also have social implications. Frequently, mental distress leads to impairment in functioning related to self-care, household maintenance, work, and social engagement. Suicidal ideation may follow compromised mental and physical well-being. To address challenges such as these, we must view treatment and supports for behavioral stressors as having a role beyond the boundary of clinical diagnoses.

To that end, with this article, we assemble a set of observations about mental well-being and the use of behavioral health care services among older adults. We then address the policy implications of those observations.

Suicide Risk And Older Adults

On average, men have substantially lower rates of mental illness than women but higher rates of suicide—and this difference is particularly pronounced at older ages. We conducted a simple analysis applying the same information from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Underlying Cause of Death Mortality Data presented in the CDC report cited above. Here, in exhibit 1, our analysis shows suicide rates for males and females ages 65 and older over the past decade and a half. We divide the population into three age-based strata (65–74, 75–84, 85 and older). Exhibit 1 makes clear the strikingly high rate of suicide among the oldest males, trending upward since about 2008.

Exhibit 1: Crude suicide rate per 100,000 older adults by sex and age groups, 1999–2021

Source: National Center for Health Statistics Underlying Cause of Death Mortality Data, Created with Datawrapper.

Note: This figure will be included in a forthcoming publication by Frank and coauthors expected in spring 2024.

Conversely, suicide rates among older women are markedly lower—with the lowest among those 85 and older. In 2021, the crude suicide rate among men ages 85 and older was 52.4 deaths per 100,000 greater than the rate among females; in other words, men experienced a crude suicide rate nearly 17 times that of women of the same age.

There are also marked differences by race and ethnicity in suicide rates among older adults. Again, analyzing the NCHS Underlying Cause of Death Mortality Data, it becomes clear that suicide rates among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic older adults are lower than suicide rates among non-Hispanic White older adults. In 2000, the crude suicide rate among non-Hispanic White adults ages 85 and older was 5.6 times greater than the crude suicide rate among non-Hispanic Black adults of the same age group, rising to nearly 7.0 times greater by 2020. In our sample, non-Hispanic White adults ages 85 and older generally had the highest suicide rate across time. Although data were not available to study suicide rates by age group, race, ethnicity, and sex directly, these trends are driven primarily by the high suicide rate among men.

We note that the death rate from suicide among all American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN) adults is significantly higher than non-Hispanic White adults. However, due to data limitations, we were unable to study suicide rates among AIAN older adults at our age thresholds.

#James Donaldson notes:

Welcome to the “next chapter” of my life… being a voice and an advocate for #mentalhealthawarenessandsuicideprevention, especially pertaining to our younger generation of students and student-athletes.

Getting men to speak up and reach out for help and assistance is one of my passions. Us men need to not suffer in silence or drown our sorrows in alcohol, hang out at bars and strip joints, or get involved with drug use.

Having gone through a recent bout of #depression and #suicidalthoughts myself, I realize now, that I can make a huge difference in the lives of so many by sharing my story, and by sharing various resources I come across as I work in this space. #http://bit.ly/JamesMentalHealthArticle

Find out more about the work I do on my 501c3 non-profit foundation

website www.yourgiftoflife.org Order your copy of James Donaldson’s latest book,

#CelebratingYourGiftofLife: From The Verge of Suicide to a Life of Purpose and JoyLink for 40 Habits Signup

bit.ly/40HabitsofMentalHealthIf you’d like to follow and receive my daily blog in to your inbox, just click on it with Follow It. Here’s the link https://follow.it/james-donaldson-s-standing-above-the-crowd-s-blog-a-view-from-above-on-things-that-make-the-world-go-round?action=followPub

The Impact Of Unique Age-Related Stressors

Among older adults, a confluence of factors—such as social isolation, physical impairment, and economic circumstances—all appear to contribute to higher risks of depression, compromised well-being, and suicide. Depression is often a chronic, recurring illness. Therefore, many people arrive at older age having a history of depression that leaves them less economically secure, with less stable family and social relations, and more prone to subsequent mental health struggles. Older adults with depression in the past year are more likely to have suicidal thoughts than those without depression.

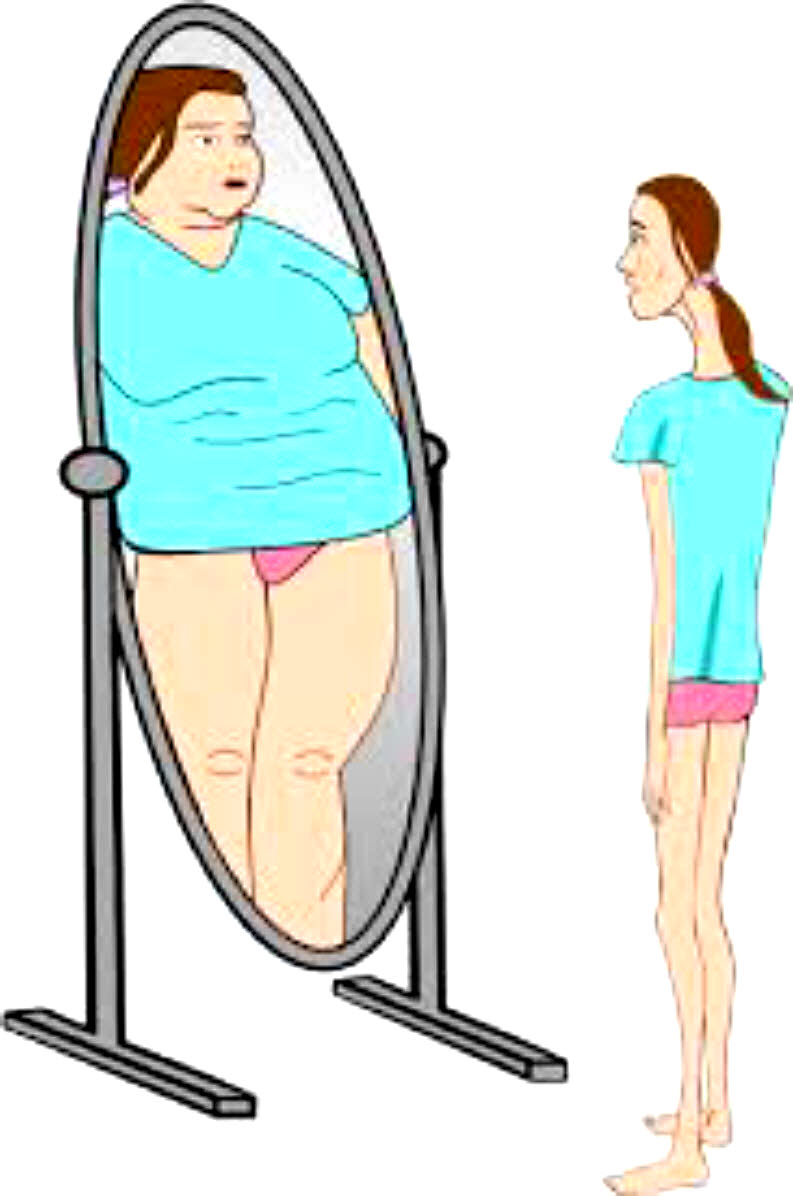

People with a diagnosable mental illness and those in treatment for a mental illness are at a significantly elevated risk of suicide, yet most completed suicides among older adults do not involve a diagnosable mental illness. Depression does not necessarily imply suicidality, and suicide is not inherently preceded by depression. Compared to younger populations, older adults are more likely to experience passive suicidal thoughts and have more varied risk factors. Recent developments in suicide prevention reflect this insight, as evidence suggests effective suicide prevention treatments target suicidal thoughts and behaviors directly, as opposed to the common practice in which mental health treatment focuses on underlying mental health disorders only. The ability to target the disparate suicide risk factors and experiences of older adults is essential to suicide prevention efforts, as it leads to a more specific screening mechanism and captures individuals who may not be receiving treatment for other mental health needs.

We examine several stressors related to clinically significant depressive symptoms (herein referred to as depressive symptoms) and mental illness, including isolation. Social isolation is prevalent among older adults. Recent research estimates that roughly 24 percent of older adults living in community settings are socially isolated. Social isolation and related loneliness can have serious impacts on health and well-being. For example, declines in social contacts can have effects on functioning that are similar to those associated with depression, even in the absence of a diagnosable case of depression.

Based on analysis of 2018 RAND Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) data, we find that older adults with depressive symptoms are about 1.4 times more likely to live alone and more than three times as likely to often feel lonely compared to those without depressive symptoms (appendix note 1).

Together, these statistics offer strong evidence of a relationship between isolation and mental well-being: Even among people who do not experience any significant symptoms of depression, indicators of loneliness and isolation are common and likely diminish well-being.

There is also consistent evidence that painful conditions developed while aging may lead to physical impairment, which is associated with an increased risk of depression. Again, based on 2018 RAND-HRS data, we find that older adults with difficulty completing two or more activities of daily living (ADLs), or essential and routine tasks associated with living independently, are more than four times as likely to have depressive symptoms than those with either one or no difficulties (appendix note 2). As individuals develop more functional impairments, rates of depressive symptoms increase.

Rates of depressive symptoms are highest for older adults with both lower levels of income and greater functional impairment. We find that among individuals in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution, those with two or more ADLs are nearly three times as likely to have depressive symptoms compared to those with fewer than two ADLs (appendix note 3). Among individuals in the top 60 percent of the income distribution, those with two or more ADLs are more than six times as likely to experience depressive symptoms than those with fewer than two ADLs. The higher rate of depressive symptoms among individuals with more physical impairment across the income distribution indicates that functional limitations contribute to depression and reduced well-being for older adults.

Behavioral Health In Older Adulthood: Definitions And Access To Care

In 2021, about 11.5 percent of adults ages 65 and older were estimated to meet diagnostic criteria for any mental illness (AMI) in the past year (appendix note 4). Slightly more than 1 percent were estimated to meet diagnostic criteria for a serious mental illness (SMI), a mental illness that resulted in substantial impairment carrying out major life activities. About 8 percent experienced substance use disorder (SUD) in the past year.

However, formal clinical definitions of mental illness or SUD contained in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) do not suitably capture mental well-being among older adults. DSM diagnoses are often based on a specific list of symptoms that occur for a given duration of time. Although these strict definitions allow for standardized diagnoses, much impairment and distress experienced by older adults may not match clinical thresholds. For example, commonly understood definitions of heavy alcohol use or binge drinking may not accurately capture the biological and social effects of alcohol use on older adults. In a similar vein, widely used clinical thresholds and diagnostic criteria for depression may be too high a bar, or the wrong bar, to reliably identify significant mental health stressors among many older adults.

This is reflected by the sizable number of older adults who make use of mental health services even though they do not meet diagnostic criteria for a mental illness. About 64 percent of older adults receiving mental health care in 2021 did not have a clinical diagnosis (appendix note 5). Complex challenges in the lives of older adults such as isolation, significant personal loss, and diminished capacity may lead to mental health care demand. These factors likely contribute to the large share of treatment resources used by people not meeting diagnostic criteria for a mental health condition.

At the same time, older adults who can potentially benefit from care face a variety of potential difficulties in gaining access to mental health treatment, regardless of having a diagnosable illness. Barriers to care include greater exposure to costs, the limited supply of clinicians with expertise in treating older adults with mental illnesses, and frequent isolation. The evidence for this derives from treatment rates among older adults that do meet diagnostic criteria for a mental illness. Overall, among adults ages 65 and older meeting diagnostic criteria, about 37 percent of those with AMI and 67 percent of those with SMI received mental health treatment in the past year; among those with SUD, this figure falls to only about 4 percent (appendix note 6). These data suggest meaningful levels of unmet behavioral health care need among older adults.

Policy Challenges And Implications

Baby boomers born between 1946 and 1964 have had relatively higher suicide rates across the age spectrum compared to other birth cohorts in the United States. Given that by 2030, there will be more than 71 million Americans ages 65 and older, the high suicide rate among this group has implications for the future. This is particularly salient in the context of the historically high suicide rates—across age groups—currently being faced in the United States.

Treatment for diagnosable mental illnesses is one important part of reducing suicide risk for some older adults—however, this alone leaves many carrying elevated levels of risk that could be reduced with evidence-based interventions. The evidence discussed earlier shows that subclinical levels of mental distress also have disruptive effects in the lives of older adults. This is evident from the associations among social isolation, loneliness, and suicide-related behaviors, and is further underscored by the high share of mental health treatment that is not associated with a diagnosable mental disorder.

Nearly all older adults interact with the health care system; this includes those who experience mental and physical impairments and are therefore more likely to have suicidal ideations. Yet, they are seldom assessed at any point for being at risk of suicide. For example, 45 percent of people who died by suicide saw a physician in the prior 30 days, and 36 percent had an emergency department visit that did not carry a diagnosis of a mental illness in the year prior to their death. These missed opportunities limit access to treatment. So do other factors, such as high costs, lack of mental health clinicians participating in Medicare, and isolation, that pose barriers to receiving mental health care overall.

Fortunately, there are some interventions that have been shown to decrease suicides among older adults. These include: increasing screening for suicidality in non-traditional behavioral health settings, such as in libraries, during pastoral counseling, or through other community-initiated care; and providing various social services and supports. Given that almost all older adults have contact with a primary care physician, primary care could be a beneficial setting to implement suicide risk assessments. These assessments should be targeted to specific risk factors for older adults, such as involuntary retirement, social isolation, perceived burdensomeness, sadness after the loss of a spouse or partner, and declining health. Screening for upstream stressors may also allow for linkage of vulnerable patients with community resources to mitigate their effects, such as meal delivery, telephone outreach, access to hearing aids and assistive devices, or transportation assistance. Furthermore, given the significantly different rates of suicide among men and women at older ages, risk screening should be sensitive to different expressions of depression or suicidality by gender.

Recent policy changes aimed at promoting access to behavioral health care in the Medicare program are a positive step in supporting older adult mental health—particularly the expansion of the provider base to include marriage and family therapists and mental health counselors, and the provision of additional payments for practitioners delivering primary care that is associated with behavioral health. These policies further integrate behavioral health care with primary care and may allow for more older adults to interact with important mental health services, yet more can be done to target risk factors specifically.

Together these observations suggest that mental health and the need for behavioral health services among older adults would benefit from a more comprehensive view. Commonly accepted definitions and risk factors for the population of adults younger than age 65 may not accurately reflect the lived experiences and needs of older adults. Access to needed mental health care must improve—including through adjustments to definitions in formal mental health treatment and increased age-specific suicidality screening. Too many older adults are unsupported in the current behavioral health landscape.