Turning the Page: After struggles, 16-year NBA vet James Donaldson wants to help young athletes shed mental health stigma

By Art Thiel

Prone upon an overmatched bed, 7-foot-2 James Donaldson was affixed with tubes and monitor patches when Lenny Wilkens walked into the room at Swedish Hospital’s intensive care unit. The former Sonics star player and championship coach, who gave Donaldson his first pro basketball job in 1980, spawning a 16-year NBA career that included an All-Star Game selection, was shocked.

“He seemed to recognize me,” Wilkens says, sounding a little shaken. “But he couldn’t speak.”

That was January 2015. Donaldson can speak now passionately, supplemented often by a dazzling smile that these days offers a fragile counterpoint to the melancholy.

At 60, he can do many things. There’s one thing he can’t do: Forget.

Eleven-and-a-half hours of emergency heart surgery was followed by a week in a medically induced coma to prevent swelling in the brain. He spent two months in intensive care, followed by more months of arduous physical and emotional rehab.

For a 35-year vegetarian – never a smoker, drinker or drugger – who stayed fit after his playing career ended in Europe in the late 1990s, his physical travail left him bewildered and despairing.

“At the time, the doctors said they were worried about paralysis, a vegetative state, strokes, all kinds of things,” he says. “On that line between life and death, I was right there.”

As Donaldson struggled to regain his physical vitality, other matters closed in.

By 2017, an IRS audit revealed he owed back taxes. A woman and her 9-year-old son, with whom he had a long-term relationship, walked away, with no further contact. His business, the Donaldson Clinic, a physical therapy practice begun in 1989 that grew to three Seattle-area locations, faltered. In February 2018, the original office in Mill Creek was shuttered.

Donaldson lives alone in a big house in Magnolia. Late last year, the “alone” part was getting to him.

“One thing after another,” he says. “Around Thanksgiving, I was really having trouble sleeping through the night. I didn’t want to face these things. When I’d wake up in the middle of the night, I’d have a lot of dark, scary, negative thoughts.

“Including suicide.”

A man who seemed to have managed the perilous transition from the celebrity-athlete life to a productive civilian life – he even ran for mayor of Seattle in 2009, finishing fourth in an eight-candidate field with more than 8,000 votes – was on the precipice.

Late in 2017, after several days of disrupted sleep, Donaldson called his family doctor, thinking he would be prescribed sleep medication. Instead, the doctor asked hard questions about the severity of his depression and his suicidal thoughts.

“He pressed me, asking how I would do it,” Donaldson says. He doesn’t own a gun, nor does he have drugs or alcohol in the house. He did say that every time he drives into his garage, he sees exposed rafters and a coiled rope.

“Been there for years,” Donaldson says. “I told him, ‘I guess that’s one way.’ He told me, ‘Because you came up with that, you have a problem. You really need to work with us, and we’ll get you through.’”

As we talked quietly in a coffee shop, the big man’s eyes filled with tears. He excused himself to the restroom.

‘He should have died that day’

An aortic dissection is a vascular disorder that occurs when the inner layer of the aorta, the large blood vessel branching off the heart, tears, and blood surges through the opening, causing the inner and middle layers of the aorta to separate, or dissect.

It’s a rare condition, often genetic, and occurs a little more often in tall people. If it ruptures, death is usually swift.

As he met up at Seattle’s Interbay golf course with friends for a round, he wasn’t feeling right, even though he recently passed his annual physical exam. Sweaty, nauseous and experiencing sharp back pain, he excused himself from the group and managed to drive himself to his doctor’s office at Ballard Swedish.

“I remember making it to his office, seeing the reception desk, and then everything went black,” Donaldson says. “I don’t remember anything thereafter for five or six days.”

Dr. Peter Casterella is an interventional cardiologist (stents and angioplasty) at Swedish Hospital on Capitol Hill. He was on duty when Donaldson was wheeled into the operating room. His job was to get Donaldson’s blood pressure under control.

“By all means, he should have died on the day it occurred,” Casterella says.

Thanks to the swift, intense work by Dr. Samuel Youseff and the cardiology team at Swedish, Donaldson survived the aortic dissection. The physical recovery was slow – he was later diagnosed with sleep apnea – yet the psychological consequences are often harder to remedy.

“What happens to people who survive things like this, is there’s a loss of part of themselves; they know they’ll never be the same again,” Casterella says. “There’s a tremendous sense of guilt: ‘I should be grateful for all these people who helped me, but all I feel is sad and depressed. And I feel guilty about that.’

“It’s very normal for people who survive a life-threatening illness. This is part of what happens to people who adjust to what the consequences are.”

Apart from health matters, other consequences kept piling up in his mind. While bedridden, Donaldson talked about what he called a “premonition.” Casterella said it was a not unusual reaction to a near-death experience.

Donaldson described a mental image that had him looking down at himself as he flipped through pages of a photograph album.

“I’m looking at all the great things I’d done in my life to that point – friends, family activities,” he says. “Then I turn the page, and it’s totally black. At that point, I knew I was gone. I knew I wasn’t going to make it.”

Donaldson said he heard a voice he chose to call God’s. The voice told him to have faith and turn the next page. He did. The page was black.

“So I’m starting to argue with God,” he says. “I’m saying, ‘Wait a minute. I’ve taken care of myself. I’ve always tried to do the right things. I’m only 57. What happened? I thought I’d be 85 or 95. My dad is 92 and still going.’

“God said, ‘James, I told you, have faith. Turn the page.’ I turned it. It, too, was black. I knew I was gone then.”

Donaldson paused, teared up, and resumed his story.

“It was so real. I was fighting, and at the same time I was at peace. If God was calling me away, I was totally OK with that. But I was fighting.

“Again, I heard God’s voice: ‘I told you, James, have faith. Turn the other page.’ I didn’t want to do it, you know? But somehow, I turned the next page. It, too, was black.

“But after a few seconds, some faint images started appearing. Pictures of me, of friends … It started becoming more vibrant, real. Like regular photos. I knew at that point I’d be OK.

“That was a tough thing. Real tough.’”

Some help from his friends

Quarterback Jack Thompson was a freshman at Washington State in the fall of 1976 when another freshman – “so tall and soooo skinny” – walked into the Cougars weight room after a prep hoops career in Sacramento.

“I remember thinking, (coach) George Raveling must see a lot in this guy,” says Thompson, who as the ‘Throwin’ Samoan” became one of the greatest sports figures in WSU history. “But skinny as he was, nobody outworked James Donaldson.

“By the time I left Pullman, he had totally changed his physique. When I saw him in the NBA, I said, ‘Wow.’ He made himself indispensable.”

Circumstances now force upon Donaldson another transformation. He’s had to learn to reach out and ask for help, a tough chore for many men who pride themselves on self-reliance.

Raveling, the bombastic Cougars hoops coach from 1972 to 1983, who later coached at Iowa and USC before becoming a global marketing director for Nike, predicted the change won’t be easy.

“James by nature was not a gregarious person,” says Raveling, 80, by phone from his Los Angeles home. “Even when he played for me he was an introvert, tending to keep things to himself.

“James has always had a wealth of potential … and his intellectual skills are much richer than he realizes. He quickly understood what he didn’t know and was coachable, teachable and a hard worker. Those are three fundamental skills that escalate growth.

“Now he needs to remember those things and reinvent himself.”

Raveling, Thompson and Wilkens are in a circle of people Donaldson has connected with in an effort to help him navigate the setbacks following the surgery.

“It saddens me to see what’s happened,” Thompson says. “He’s one of the more cerebral athletes I’ve been around. Yet he had a string of things happen to him, and he mentioned his thoughts about suicide.

“When we last spoke, he was heading in a different direction and said he had a better handle on things. He values his friendships, and it’s important that we be there for him.”

Under a doctor’s care, and with anti-anxiety medications, Donaldson’s enlistment of friends made a difference over the holidays.

“Even though I’m not gregarious, I’ve always treasured friendships,” he says. “It was natural for me to reach out to them for more than surface talks. I turned to them and the medical professionals, and they were there for me.

“They asked what they can do. I said, ‘Maybe you could just call occasionally and check in on me. I live a life where people call on me wanting something. How about just calling me and seeing how my day is going? Check in to make sure I’m not going through anything too heavy.’

“They’ve all responded: ‘We’ll be there, even at two in the morning.’ I was sending out distress text messages, obviously crying out for help. That helped me get through. My friends made me realize they will miss me.

“When I was in the midst of that, I really did not think anyone would miss me.”

After the holidays, another test for Donaldson: the Jan. 16 suicide of Washington State junior quarterback Tyler Hilinski.

The inexplicable hits home

Shock over the death of a popular 21-year-old seemingly at the apex of college life still lingers in the Palouse, partly because the motives behind self-inflicted gunshot were neither foreseen, nor subsequently explained. Mental health issues can be diabolical that way.

Even though he never met his fellow Coug almost two generations younger, Donaldson had no shortage of empathy.

“I was feeling better, but Tyler’s situation brought back some things,” he says. “I was just imagining a 21-year-old with so much ahead of him, and I’m in the fourth quarter. He thought he had no one to talk to.

“It’s a lot of pressure. Friends and family think he’s a big star. Who understands that better than a former athlete?”

Hilinski was set to succeed Luke Falk, the Pac-12 Conference’s all-time passing leader, in the fall. The two were close. Falk echoed Donaldson’s sentiments when he met reporters at the Senior Bowl in Mobile, Ala.

“At times, we feel like we can’t express our emotions because we’re in a masculine sport,” Falk says. “Him being the quarterback, people look up to you as a leader and so he felt, probably, that he really couldn’t talk to anybody.

“So we’ve gotta change some of that stuff. We’ve gotta have resources and not have any more stigma about people going to them.”

The seemingly inexplicable suicide of a burgeoning college football star is part of a growing nationwide conversation about mental health among athletes. Even if it seems less so to some fans, athletes are no less susceptible to problems.

“People look at athletes and entertainers on the outside as having it all together,” Donaldson says. “On the inside, we can be as torn up as the next guy, or worse.”

As much as colleges and pro sports franchises invest in the physical welfare of athletes, there is not the same the commitment to psychological well-being, especially at a young age. Sports, it seems, are so much about the here and now.

“Most college and pro athletes don’t have a personal development strategy,” Raveling says. “They walk suddenly into a life full of money and people tugging on them. They put all their energy into the present, not the future. Many don’t think of the future, and of their mental well-being.”

But the social taboo, especially among men, against open discussion of mental health, seems to be changing.

In the middle of a personal-best season, Raptors forward DeMar DeRozan told the Toronto Star that he has been dealing for years with depression.

More intimately and expansively, another NBA All-Star, Kevin Love of the Cleveland Cavaliers, wrote a first-person essay on The Players’ Tribune. Love chronicled a panic attack he had during a Nov. 5 game. He described his bewilderment, his reluctance to seek counseling, then positive results after a successful series of sessions with a mental health therapist.

“If you’re suffering silently like I was, then you know how it can feel like nobody really gets it,” he wrote. “Partly, I want to do it for me, but mostly, I want to do it because people don’t talk about mental health enough. And men and boys are probably the farthest behind.

“I know it from experience. Growing up, you figure out really quickly how a boy is supposed to act. You learn what it takes to ‘be a man.’ It’s like a playbook: Be strong. Don’t talk about your feelings. Get through it on your own. So for 29 years of my life, I followed that playbook.”

Earlier this month, another Players’ Tribune first-person came from 13-year NBA veteran Keyon Dooling, who told of a trigger moment in a Seattle restaurant that evoked the horror of sexual abuse he experienced as a 7-year-old but kept hidden throughout his adult life.

The headline on Love’s story captured the truth: “Everyone is going through something.”

A way forward

The morning after learning of Hilinski’s suicide, Donaldson woke with an urge to tell the story of his own struggle with depression and suicidal thoughts. He wanted to help re-write the playbook Love mentioned.

“Something was tugging at me,” he says. “Tyler can’t tell his story, and telling his story is nothing I want to try to do. But his death motivated me to make sure my support was around me – friends, doctors, medications – everything I needed to fight back from a very dark place.”

A longtime member of Mount Zion Baptist Church in Seattle’s Central District, Donaldson recalled the words of Rev. Dr. Samuel B. McKinney, who pastored the church for 43 years until his death April 7.

“I remember him saying, ‘Even if you think you’ve gone through life mostly problem-free with few challenges, just keep on living,’” Donaldson says. “Sooner or later, something will hit you – part of the great challenge of a long life. He lived a great one, but at the end he was 91 and in a wheelchair, housebound.

“We all will face issues that are mentally devastating.”

Donaldson has found reward in purposefully sharing his story among people he knows best: athletes, whom he also knows are among the least likely to seek help.

In February, he was re-elected to a three-year term as a member of the board of directors of the NBA Retired Players Association, where he is pursuing mental health initiatives with the NBA.

He also is CEO of a startup business called Athletes Playbook, a mentorship program made up of veteran athletes helping younger ones. Focusing on scholarships, life mentoring and degree completion, the website says, “Our community of former professional athletes will provide a playbook for athletes, parents and coaches for high achievement in sports and life.”

The subscription-based business seeks to develop connections with students, coaches, high schools and colleges that need help reaching athletes reluctant to talk about their anxieties as well as their aspirations.

The concept has led to conversations with athletic department officials at Washington State and the University of Washington about creating a non-clinical program to help break down the isolation some athletes feel in big-time programs.

“Mental health for student-athletes is my new advocacy,” he says. We’re trying to find out what a program looks like, and try to create a model. The long-term hope is to do it with more schools.”

The discussion and the potential ways to help have done wonders for Donaldson’s own outlook.

“I’ve gone from a place of hopelessness and despair to a place of hope,” he says. “It’s night and day. There are opportunities ahead. I’m striving for things, making new friends. I have a reason to get up and live. A few months ago, I had none of that.”

He intends to be honest with young athletes. Progress, he will say, is often not steady. For older athletes he meets via the Retired Players Association, he is also honest about managing later-life stages, when body and mind don’t respond as they once did.

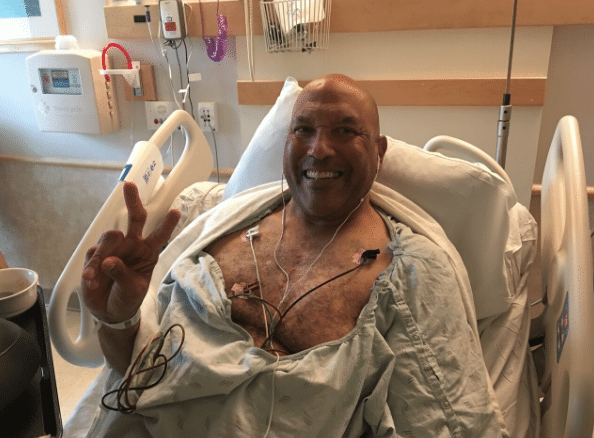

Donaldson was hospitalized last week for a heart irregularity. His medications were adjusted, and he is back home, ever more mindful.

“Most of my days are good, but there’s the occasional one …” he says. “On a recent Friday, on the end of a long week, I was exhausted. I suddenly wanted to end it all. How I keep reverting to that, I don’t know. I still have a little sense of impending doom.

“We know to expect the physical changes. But managing the mental part of the changes is a hard thing. That is where I hope to help.”

Donaldson doesn’t have all the answers, but he’s joined those who are breaking through the shame surrounding mental health in sports. He is no longer alone. With help, he keeps turning the page.

Art Thiel was a longtime sports columnist at the late Post-Intelligencer in Seattle. He co-founded Sportspress Northwest, a digital daily news and commentary site that chronicles the Seahawks, Mariners, Sounders and University of Washington sports. He recalls when George Karl and Gary Payton stopped arguing long enough to produce splendid springs of playoff basketball. Follow him on Twitter @Art_Thiel.

(Top photo: Nancy Hogue/Sporting News via Getty Images.)

Keep turning the page, Brother!

You have a purpose and a reason to KEEP the momentum of the Life that God is breathing into your body.

With every heart beat, LIVE and Love as best you can!

Blessings!

Greetings Patti,

Thank you so much for your encouraging words and keeping me in your thoughts and prayers.

Take care and have a wonderful day.

James

Hi James I am one of your brother high school fans . I remember when this happen. Matt was very worried about you. I think what you are trying to do is a great thing and you have my support and you are in our prayers. Great to see and hear you are doung better. Stay strong my best friend big brother.

Good morning Bruce,

I hope all is well with you and that you have a wonderful day. Yes, I remember Matt talking about you from time to time not sure if I’ve ever met you in person other than perhaps just in passing.

Anyway, thanks for your encouraging words. I hope to help quite a few people out there as best I can.

Take care of yourself and have a wonderful day.

James

James,

sorry I couldn’t be there for you my friend. We talked a lot when I was living there and played a lot of golf. I think what you are doing is great. Many can benefit from what you have gone through. Keep standing tall and know that my prayers are with you.’

George Wilson

You have a great Story tell James. Its so good you are committed to helping others. So many People have Mental Health issues that go untreated. Just watched a Muscian named Josh Wilson on the 700 club who suffers Panic Attacks. He also has come forward. Keep up the good work.

Found this article on Stan Coes Facebook

John Stimac